Public Realm Performance

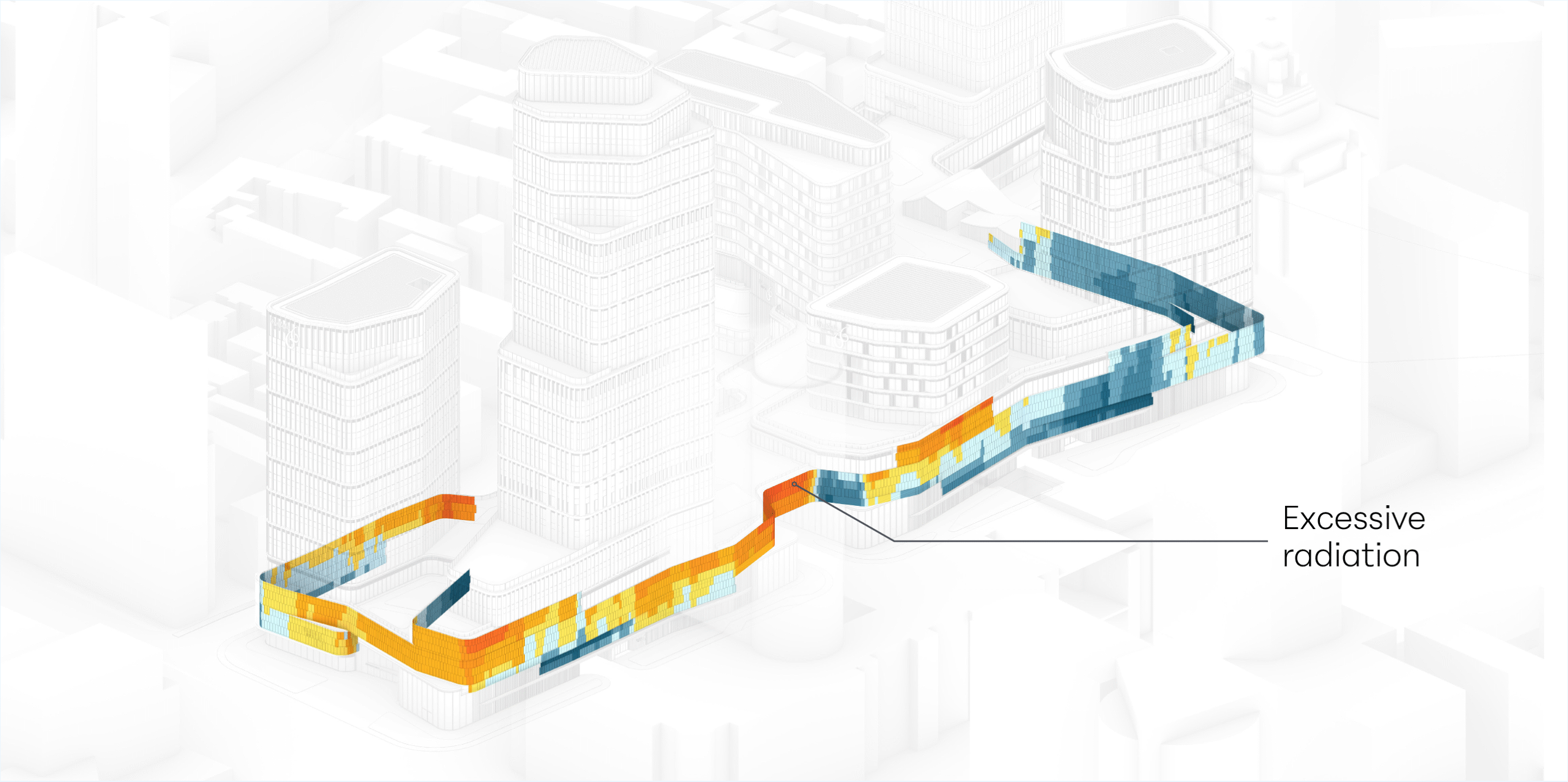

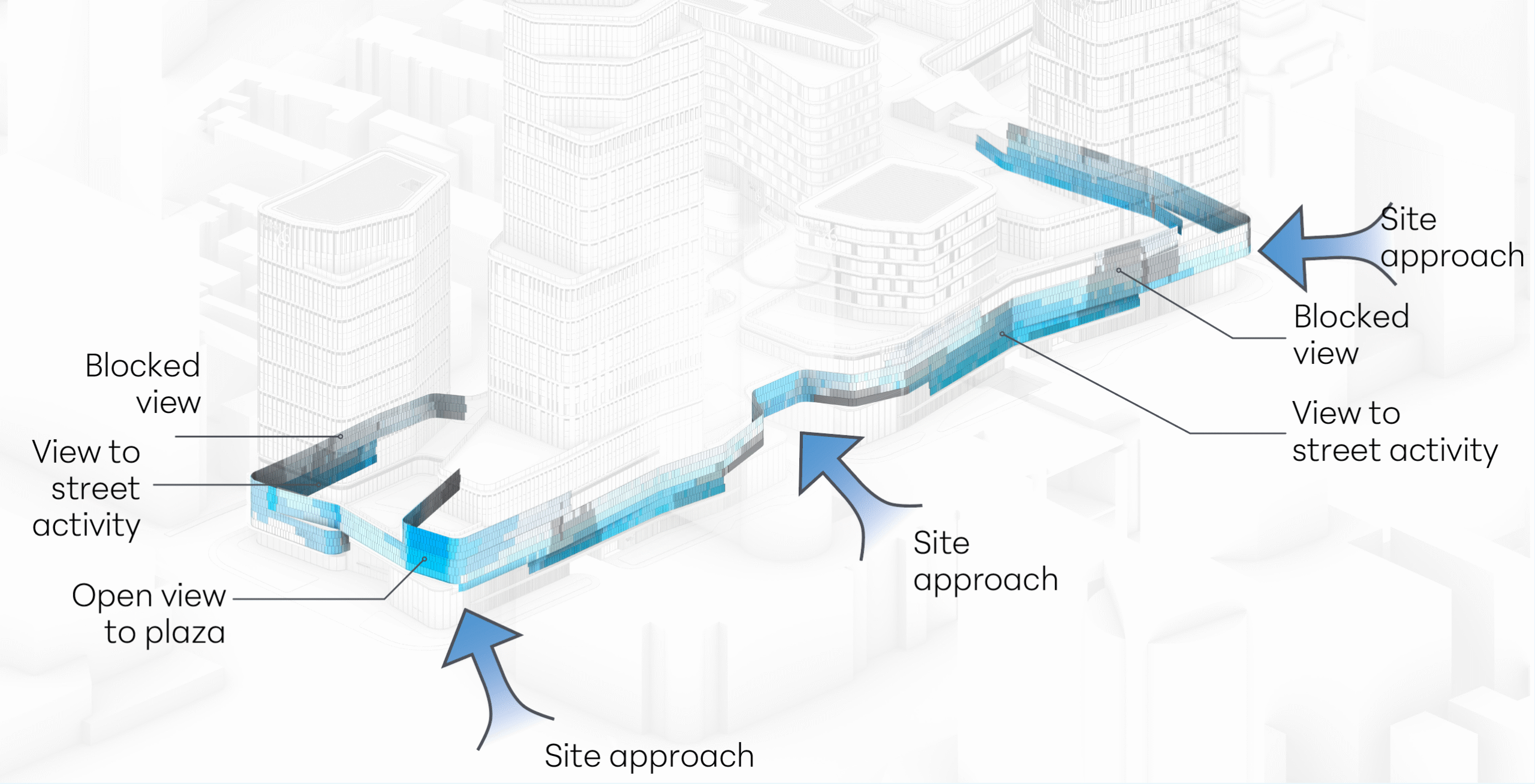

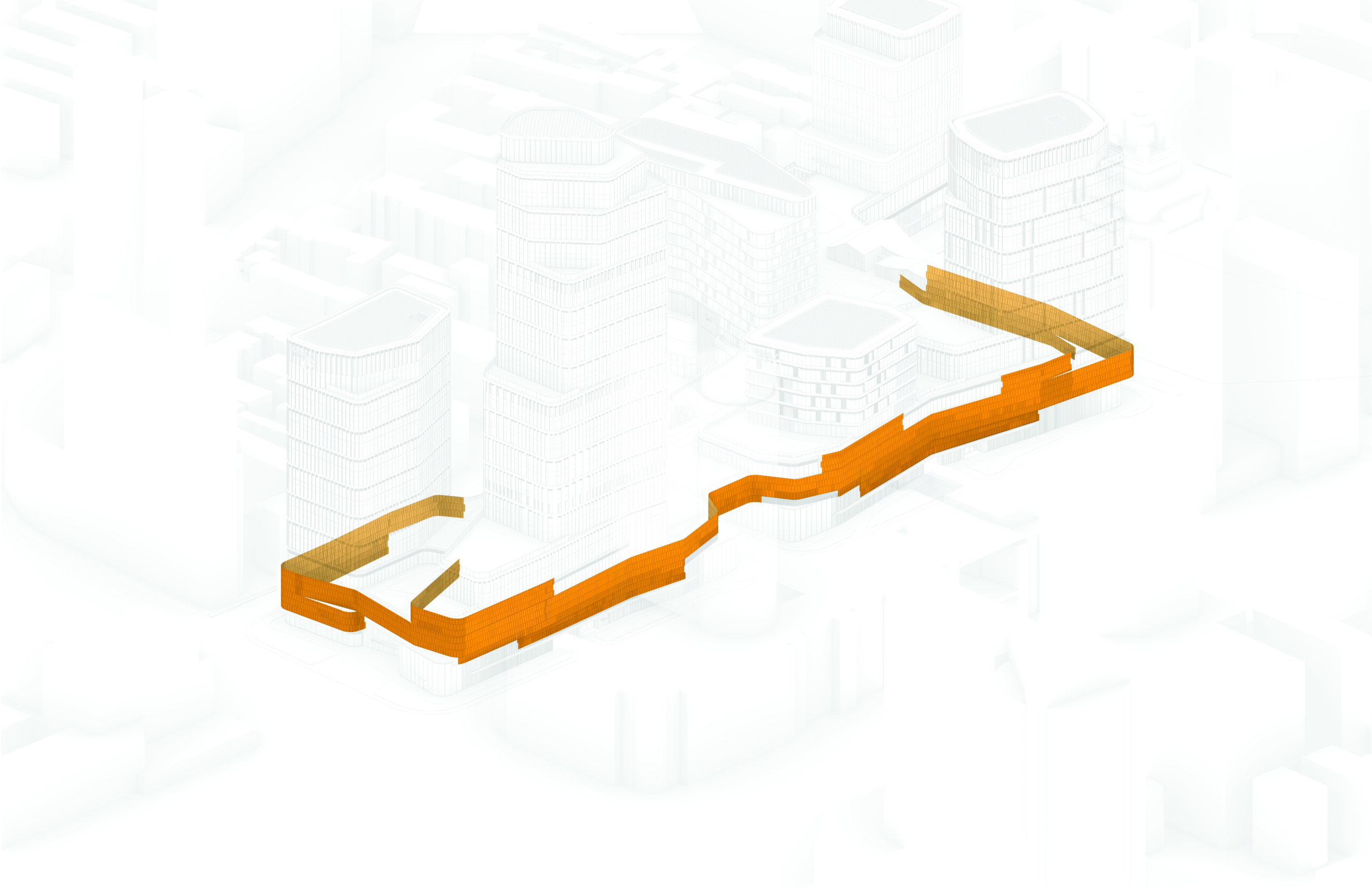

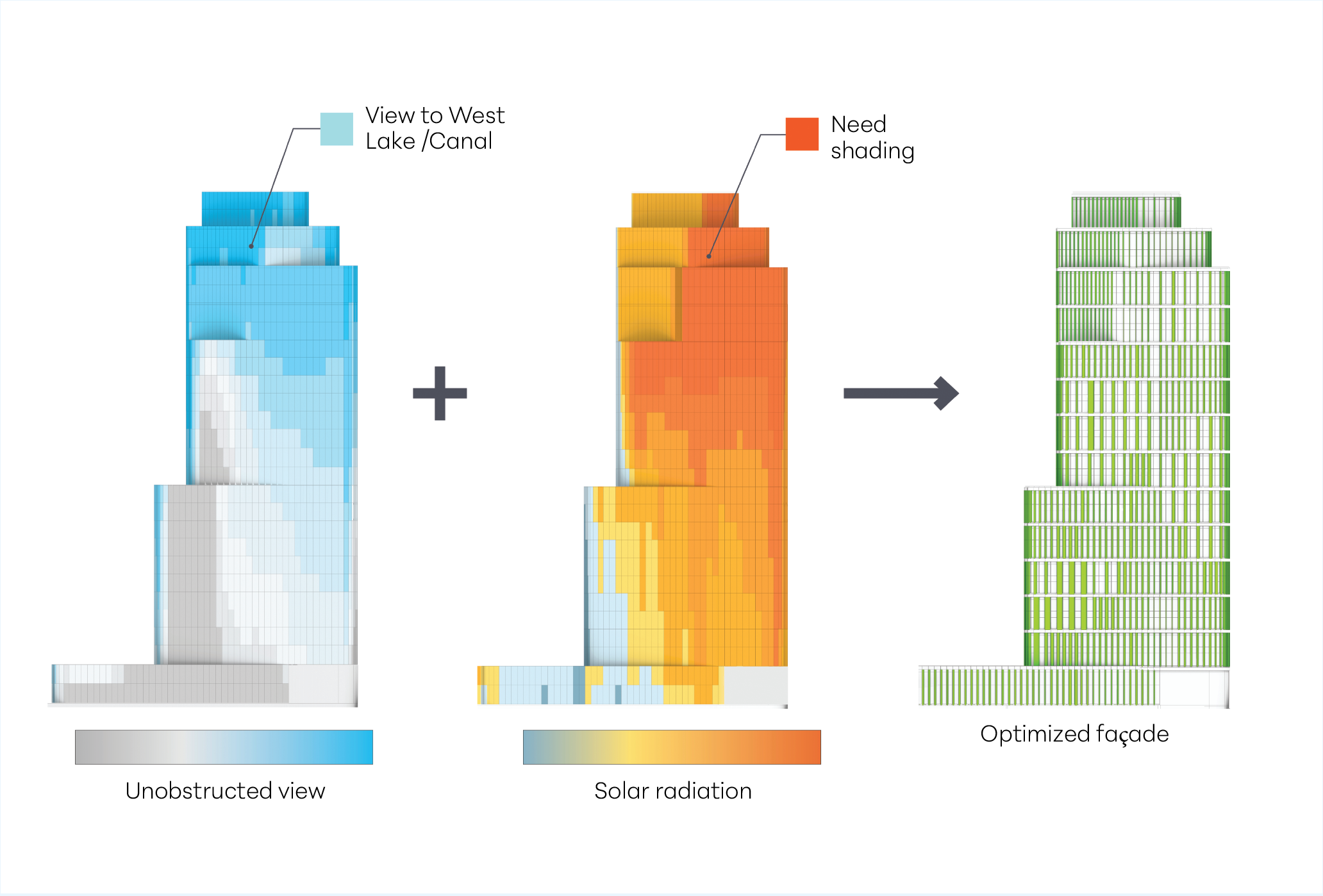

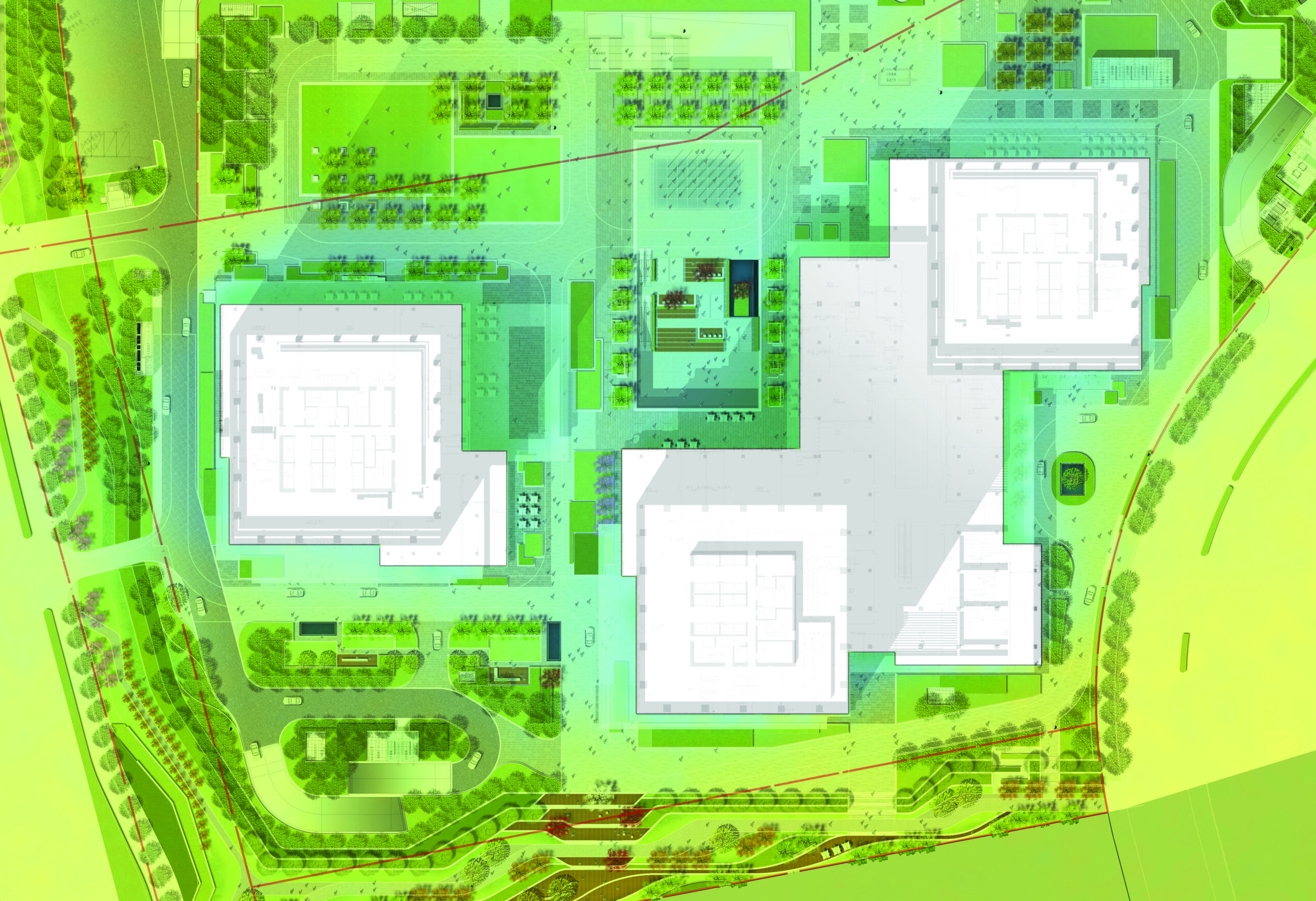

As outlined in the introduction, the application of computational modeling has expanded beyond building performance to include public realm performance, placing a new emphasis on how data can inform the design of more active, walkable, and vibrant spaces. A data-driven approach to placemaking focuses on three key elements: understanding where people are likely to go (pedestrian routing analysis), what they are likely to see (visibility analysis), and how they are likely to feel (outdoor thermal comfort analysis). Unlike traditional building-focused performance metrics, these analyses prioritize the human experience, offering insights that inform decisions such as building massing, the placement of circulation elements, programmatic organization, and the design of shading and landscape features.

By leveraging these tools, architects and planners can create public spaces that are not only functional and comfortable, but also socially engaging, fostering connectivity, accessibility, and a sense of place.

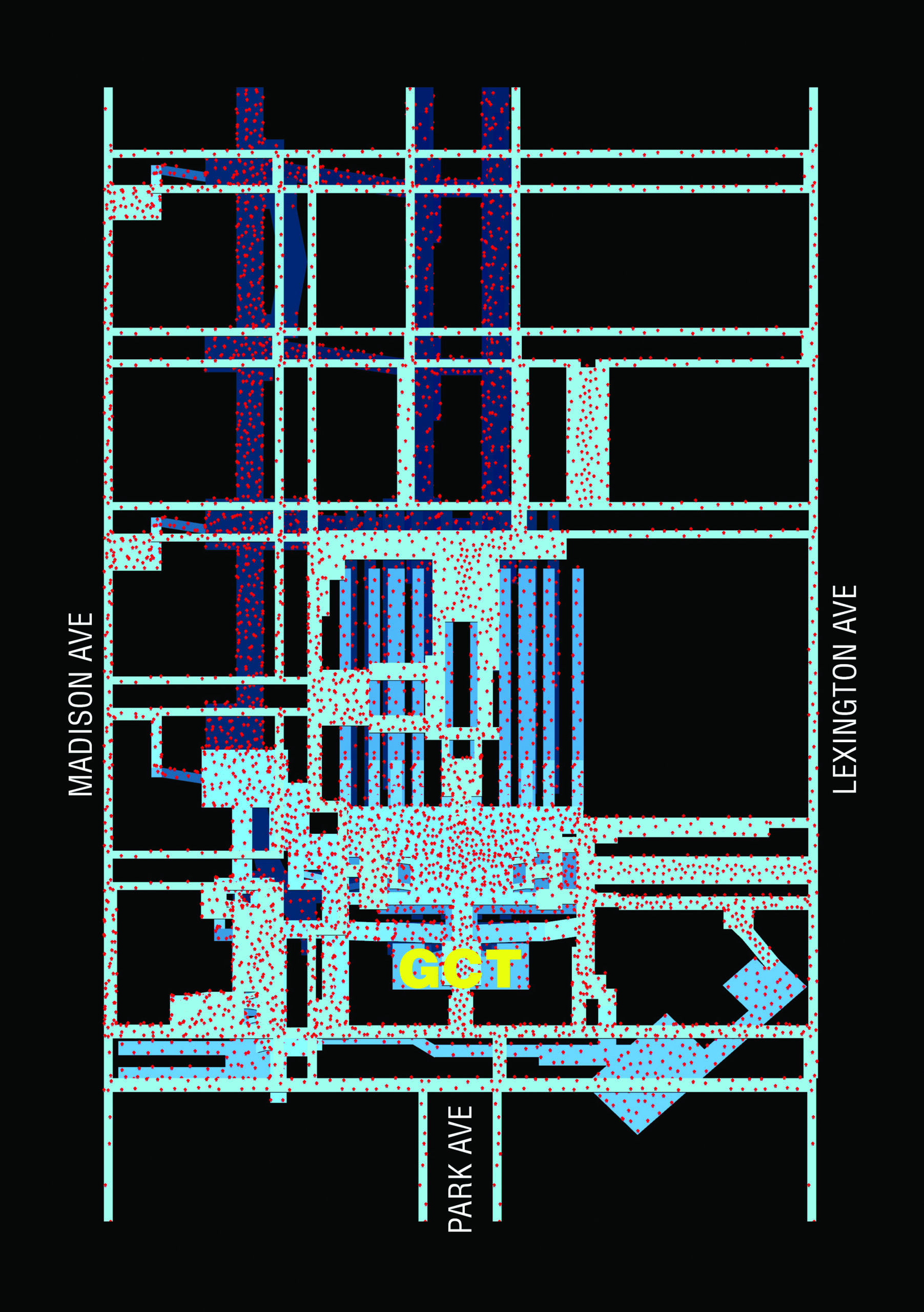

One Vanderbilt Avenue, New York City

One Vanderbilt Avenue, a 59-story office building in the heart of Midtown Manhattan, is directly connected to Grand Central Terminal, linking commuters to Metro-North, the Long Island Rail Road (LIRR), and the subway. A primary driver of the design was reducing both existing pedestrian congestion and the anticipated increase in foot traffic from the introduction of the LIRR connection. To address this, the design team employed advanced computational tools to simulate pedestrian routing under both current and projected conditions. These simulations informed key design decisions about how One Vanderbilt’s connections to the transit system could most effectively alleviate congestion (see Figure 8).

The process required integrating data from a neighborhood-wide Environmental Impact Statement, modeling the complex 3D pedestrian network, and applying origin/destination pedestrian modeling simulations to capture movement patterns. Based on this analysis, the design incorporated strategic interventions such as pedestrianizing Vanderbilt Avenue, setting back and angling the ground floor to expand circulation space, and widening underground connections. As a result, One Vanderbilt Avenue saves commuters an estimated 123,000 hours per year that would otherwise have been lost in pedestrian congestion.

This level of congestion reduction and optimization was only achievable through computational modeling, which enabled the design team to quantify movement patterns, anticipate future challenges, and propose targeted solutions that enhance both the commuter experience and the building’s urban integration (see Figure 9).